How To Avoid The Salesman's Hype And Focus On What's Best For You

Key Ideas

- Why life insurance is a negative expectancy bet for the majority of consumers

- The problem with mixing investing with life insurance

- 4 concerns you should have about whole life insurance

- 7 basic terms and features of whole life insurance you need to know

- Why you may not benefit from compound interest with whole life insurance

- The hidden consequences behind tax-free whole life insurance loans

- 4 common, persuasive arguments from whole life salesmen and why they're wrong

What’s the most popular type of life insurance sold in the U.S.?

If you guessed term life insurance, you’d be wrong.

Despite the well-established conventional wisdom that you should “buy term and invest the difference,” the reality is whole life insurance sells the doors off term. The numbers aren’t even close.

According to the American Council of Life Insurers (ACLI), in 2014, 63.7% of all individual policies sold in the U.S. were whole life, compared to just 36.3% of policies being some type of term coverage.

This fact is even more disturbing because you’d be hard-pressed to find anything positive written about whole life insurance unless you happen to prowl insurance agent or insurance company sites that profit from selling that type of policy to you.

And yet 63.7% of all policies sold are whole life. Amazing!

This article will give you a deep understanding of whole life insurance – its benefits, pros & cons, tax treatment, and use for retirement income – so that you can decide for yourself what best fits your situation.

You’ll get everything you need to combat the insurance salesman’s hype so you can make a smart decision, independent of their influence, as to which type of life insurance is best for you.

Get This Article Sent to Your Inbox as a PDF…

Whole Life Insurance – The 30 Second Elevator Speech

The writer in me is always impressed with the salesman’s pitch and how they manage to frame their product in the most favorable light.

It’s an art form, so let’s consider the typical pitch for whole life insurance before dissecting it.

- You can “contribute” as much premium as you like (not subject to limits like an IRA or 401k), so there’s no limit on your tax-deferred growth.

- Your policy has a built in “cash value” account, where you’ll enjoy a guaranteed minimum interest return, tax-deferred growth, and tax-free access to your funds via policy loans.

- What's more, should you die while you hold this account, your policy value will blossom into a much larger cash benefit, which your beneficiaries will receive without paying any income tax.

Not a bad pitch, eh? Now you know why it sells so well.

Entire books have been written indoctrinating laymen about how whole life insurance is the perfect vehicle for tax-free accumulation and distribution of retirement income.

But if there’s one lesson you should take from my writings, it's that the world of personal finance is rarely so simple. Whenever a salesman gives you an over-simplified, glowing analysis, it should always serve as a warning flag that you need to dig deeper and uncover the whole truth.

Life Insurance Common Sense Test

Before we analyze whole life insurance in depth, we must first set a framework for the arguments so we're grounded in obvious business truths.

The reason this is essential is because, I have to warn you, this is going to get complicated. The insurance companies designed it this way to help sell their products (I'll explain this below).

If you're not thoroughly grounded in inviolable, mathematical truths, then you can easily get distracted and swayed by their persuasive arguments.

The essence of life insurance is you give the company your money in the form of policy premiums and they give you back a package of benefits in exchange.

The value of those benefits, on average, must be less than the value of the policy premiums you paid, after factoring in the time value and investment return on the money, in order for the insurance company to profit and pay salesmen commissions.

In simple language, that means that on average, the general population would be better off independently investing the money, rather than giving it to the insurance company and having them invest it in exchange for a contractual package of benefits.

Or stated even more simply, the contracted benefits package offered by the policy must, on average, have a lower value than the money you pay to the insurance company for those benefits.

If this weren’t true, then the actuaries designing these complicated investment contracts would get fired, and the insurance company would lose money and eventually go out of business.

This isn’t some conspiracy theory. It’s just irrefutable business common sense. It's inviolable math.

Let me be clear that this inviolable math doesn't mean that you can't win with life insurance. You absolutely, positively can win.

Insurance is an actuarial process where the minority can win and the majority must lose in order to pay the salesman's commission and leave a profit for the insurance company.

Okay, now that you have the basic life insurance business equation down, defining it as a negative expectancy bet, on average, for all policy holders, where some will win and the majority must lose, we must add an additional layer of complication to deal with investment products wrapped inside life insurance.

When investments are involved, the benchmark for judging whether the product is beneficial or not rises to the level of competing investment returns, since that's the alternative you would invest your money in if life insurance wasn't there.

In other words, you really have two things going on when analyzing the life insurance purchase decision.

You've got life insurance in its simplest and most traditional form – a risk management tool – where you pay the company to provide a benefit to support your dependents (or achieve other financial objectives) in exchange for a defined cost should you meet an untimely demise.

This cost is a known, negative expectancy bet that you hope you lose on by living a full and long life. It's similar to homeowners insurance and liability insurance, where you transfer risks you can't afford to accept to an insurance company in exchange for a fee. The insurance company then earns a fair business profit for providing this valuable risk management service. Examples include term life insurance and guaranteed universal life.

However, combining life insurance contracts with investment contracts, like with whole life insurance, is a different animal entirely.

The problem is the insurance company invests the capital you send them in the same stuff you and I can invest in on our own – stocks, bonds, real estate. They have large pools of capital and earn market based returns because they are the market. The only problem is they stand in the middle collecting fees and paying commission which means the net return to you as a policyholder must be less than competing low cost alternatives. The high fees and commissions virtually assure this.

That means, by definition, their investment products are at a competitive disadvantage to conventional investments with lower cost structure and less commissions.

Numerous research studies have proven that cost is top indicator of long term investment outperformance relative to the averages, and life insurance companies are at a competitive disadvantage on costs, which places them at a competitive disadvantage for selling their wares based on investment return.

Are there exceptions? Yes, but that doesn't change the math, that on average, this must be true for the majority. Remember, insurance is always an actuarial process where exceptions will exist, but the majority defines the rule. It's the nature of the beast.

So how do the insurance companies compete in the investment arena when they're at an inherent investment return disadvantage due to costs?

The solution is genius.

They roll out a litany of incredibly complicated investment products with incredibly complicated benefits so that even the experts can't agree on what's best or even how to analyze them. The insurance company obfuscates the truth through complication.

The game is simple. Professional actuaries who live and breathe this stuff full time create packages of benefits associated with complicated rule sets.

The package of benefits is used to sell the policy to the consumer, and the complicated rule set is used to ensure that the policy is a negative expectancy bet for the majority of consumers (net of competing, low cost investment returns), resulting in a profit for the insurance company.

Whenever you meet a complicated investment, always know one thing with absolute certainty: the complication doesn’t exist without a reason.

Each term changes the mathematical expectancy of the investment, and I guarantee it doesn't change it in your favor. When it comes to life insurance as an investment, always know that the devil is in all those complicated details and fine print that you don't understand (but they do).

The investment rule this violates is you should never invest in anything you don't fully understand because that means you can’t define the expectancy of your investment. Life insurance investment contracts are so complicated that even the experts disagree. It's fraught with controversy.

The key point to carry throughout the rest of the analysis in this article is that there’s two things going on here:

- Traditional life insurance, which is simple to understand, is a known negative expectancy bet that's totally acceptable because you're paying for the privilege of transferring risk you can't afford to accept. It's very similar to liability insurance and homeowners insurance. You buy it hoping you lose, and that's okay.

- Life insurance as an investment product is very different. It's so complicated and filled with so many rules, each of which changes the expectancy of the bet, that advanced expertise beyond the capability of most consumers it's sold to is required to sort it out.

This gives us two simple rules that we'll carry throughout the following analysis:

- Traditional life insurance (examples include Term and Guaranteed Universal Life) is a wise purchase when the death benefit and risk transfer are justified by the price.

- Investment products wrapped inside a life insurance policy (Whole Life) can be a wise purchase when the ancillary benefits (tax advantages, asset protection, employee retention, etc., etc.) are justified by the price.

In other words, savvy consumers are not buying life insurance investment products for their investment value. Instead, consumers are accepting the negative expectancy (on average) against competing alternatives for your capital in exchange for an ancillary benefit built into the contract that they value enough to justify the cost.

As a consumer, you must always know that every policy is designed by the company to be a negative expectancy bet for the majority of the purchasers, and positive expectancy bet for the insurance company.

You are buying something designed to make you lose money relative to investment alternatives, so have your eyes wide open and do your due diligence.

This is not a conspiracy theory. It's just business. It's baked into the cake by inviolable math.

It doesn't make life insurance bad. It just means you have to really know what you're doing.

The Other Side Of Whole Life Insurance That The Salesman Didn’t Tell You

With that framework in place, let’s now look at some of the complicated details left out of the salesman’s persuasive arguments above that change the expectancy of the investment…

When you buy whole life insurance, you become contractually obligated to make contributions every year, and cannot waiver.

If you miss a contribution, the rest of your account value is penalized. If you take money out of your investment, you have to pay it back plus interest, and if you don’t pay it back, you could be in jeopardy of losing all of your investment.

You won’t break even on your investment for the first 10 years because of all the costs and fees associated with your investment, and for the same reason, you’ll probably earn significantly less than competing investments over the long term.

Doesn’t sound quite as alluring, eh? But wait, it gets better…

When structured properly, most “distributions” you’ll take (including gains), are tax free.

However, if you ever decide to cancel your account, withdraw 100% of the funds, or even need access to more money than you had anticipated, you could have to pay income tax on all the “tax free” gains you’ve ever taken from the investment.

Lastly, if you die with funds in your account, the company keeps your investment.

This, in a nutshell, is the dark side of whole life insurance the salesman doesn’t reveal. As I said, the devil is in the details, and each detail was created by the insurance company actuary with the sole purpose of managing the expectancy of the contract.

On top of that, some additional concerns you should have about whole life insurance include:

- It’s confusing – not just for the average Joe consumer, but for anyone who doesn’t live and breathe life insurance. Heck, even the people who live and breathe life insurance disagree about the stuff in this article.

- It’s expensive (as a pure lifetime insurance coverage play, it usually costs 2-3x as much as guaranteed universal life).

- The tax and liquidity benefits are often grossly overstated.

- And it offers a lower rate of investment return than competing investments.

With that said, there are extremely rare instances where whole life insurance makes good business sense for the consumer. It’s not always bad because remember from earlier, it's an actuarial outcome where the minority can win but the majority must lose to pay the salesman's commission and still provide profit to the insurance company.

However, most insurance experts (except, of course, the whole life salesman) will generally agree that if you have a whole life policy (and are healthy), you should consider the possibility of transferring the cash value into a lower cost, lifetime guaranteed coverage plan, such as a guaranteed universal life insurance contract.

It costs you nothing to look carefully at the numbers to see if it makes sense for you.

Whole Life Insurance – First, the Basics

The key difference between term life insurance and whole life insurance is term offers low cost protection with guaranteed level premiums for a fixed duration, typically 10, 15, 20, or 30 years; whereas whole life insurance offers lifetime guaranteed coverage with the additional benefit of accumulating cash values.

In other words, whole life is a mix of investment and life insurance, and that’s what causes all the complication. Because it's an investment product it's held to a whole different standard. It must provide positive expectancy, and it must outperform competing investment products if your objective is investment return.

The other problem with mixing the investment product with life insurance is the complexity. Just look at this list of whole life insurance features:

Basic whole life insurance features:

- Fixed Level Premiums – Premiums are guaranteed to stay level for life, or you can schedule the premiums to be “paid up” by a certain age, such as 65. If you miss a payment, cost of insurance is deducted from your cash value, and if you don’t make up the payment, that can lead to a reduced death benefit.

- Lifetime Guaranteed Face Value – The benefit amount is fixed for life. It cannot decrease as long as the owner continues to make timely premium payments.

- Cash Value Account – Besides the life insurance component, whole life policies contain a cash value account associated with the policy, from which fees and cost of insurance are paid. The cash value account typically earns a minimum, guaranteed interest and accumulates tax free.

- Tax-Free Access to Funds – Whole life cash withdrawals are tax free until you reach the cost basis, as withdrawals are treated with FIFO (first in – first out) accounting rules. Most people, however, borrow from their policy cash values to keep their cash value account in tact and earning interest, but are charged interest on policy loans until the loan is paid back, similar to how a home equity line of credit works.

- Dividends – Most insurance carriers pay dividends to their policy holders. Owners can take these dividends as cash, apply the dividends to pay down their premiums, or have them purchase “paid-up additions,” which essentially buys them additional life insurance, pushing up their cash value and death benefit. Dividends are not guaranteed, but most companies pay them every year without fail.

- Commissions – Life insurance agents earn commissions based on the premium paid into a policy, typically between 80% to 100% of the first year’s premium. Therefore, most or all of a whole life policy’s first year’s premium gets paid to the salesperson, which also helps explain why it can take 10 years or more for your investment to break even.

- Surrender Fees – To manage the risk of paying the first year’s premium to the salesperson, most companies add a 15 year surrender fee schedule to their policies to ensure they earn back that commission, one way or another. If a policy holder cancels the policy during the first year, he would typically not expect to get back “any” of his cash value. The penalty decreases each year thereafter.

- Paid-Up Additions (PUA) – If you buy whole life from a “mutual” company who pays dividends, one of your dividend options is to purchase additional, single premium bits of additional life insurance. This is called paid-up additions, and serves to increase your death benefit (with no qualification or medical exam) and since most of the premium (approximately 90%) is funneled to your cash value, it is the fastest way to increase your cash value. Some policies also have an option (or rider) where you allocate some of your premium to purchasing paid-up additions. It's common to see individuals allocating 70-75% of their premiums to the base policy and 25-30% to PUA. The advantage in doing so is faster cash accumulation. The disadvantage is you'll have a lower death benefit, as single premium paid-up additions coverage costs more than the standard whole life coverage.

Whew! Can you already see what I mean about complication? And trust me, we're just getting warmed up on this front.

But at least, for now, you have the basic terms and features of whole life insurance.

You also understand the general framework of expectancy analysis as applied to life insurance and the actuarial reality of how the minority can win but the majority must lose relative to competing investment products. Finally, you understand how complicated features and rules are used to change the expectancy of the investment as demonstrated already just by this partial features list.

So now, you're armed with all the tools you need to take the discussion a cut deeper by analyzing the inner complexity underlying whole life insurance.

My objective is to give you a deeper understanding behind many of the insurance agent’s claims that drive whole life to dominate the life insurance sales charts so that you have a balanced perspective and can make a smart financial decision.

We'll start with fixed level premiums…

Fixed Level Premiums (aka Forced Contributions)

Let’s assume you contribute $1,000 per month into your 401K as part of your wealth plan. But then life changes and you hit a roadblock.

Perhaps you lose your job or need to provide financial assistance to a family member, and you stop making your automatic contribution for a while.

If you’re contributing to a 401k, it’s no problem. You can always stop your automatic contributions for a while until your financial situation stabilizes. You own the asset, and you’re in control.

With whole life insurance, however, that’s a big problem, especially during the first 15 years of the policy while cash values are low and aren’t earning much interest yet.

Remember, this isn’t a straightforward asset you own. Instead, it’s a contractual obligation with an insurance company on the other side.

You must understand that when you stop making premium payments to your life insurance company, they don’t stop charging you for the cost of insurance and other fees, which eats away at the cash value you’ve accumulated, and could put all the premiums (contributions) you’ve paid into the policy at risk.

Can you imagine an investment that forces you to make payments or your initial investment is at jeopardy?

Welcome to whole life insurance! Remember, it’s a contractual agreement, so the terms are whatever is defined in the contract.

And since whole life is so expensive, typically 10-20x the price of term life insurance, a lot of people can’t afford to keep their policies through all of life’s ups and downs, and are forced to let them lapse.

In fact, the Society of Actuaries conducts an annual persistency report, and the most recent one shows that:

- 12% of individual whole life policies lapse during the first year,

- 10% lapse in the 2nd year,

- 8% in the 3rd year,

- 6% in years 4-5,

- And finally drops to 4% in years 11-20, and 3.5% in years 21+.

That’s a lot of people surrendering their policies, and they’re often hit with a hefty surrender penalty, getting back a fraction of what they originally paid into their policy.

Surrender penalties are meant to discourage policyholders from directing their funds into another investment. For that reason, it’s very important that you read the fine print on any whole life insurance policy that you might be considering so you know what you’re getting yourself into for the long term.

The key point to take away is that whole life can only work if you consistently pay your premiums for a very long time.

That’s a serious potential problem because everybody has ups and downs and goes through unexpected setbacks. Any financial strategy that doesn’t allow for “life” to happen, but in fact penalizes you when it does, is not representing the best interests of the consumer.

Get This Article Sent to Your Inbox as a PDF…

Rate of Return – “Hidden” Charges and Overstated Tax Benefits

Another challenge with whole life insurance is deciphering the real rate of investment return.

While policy costs are disclosed if you look hard enough, few readers have sufficient financial math skills to convert those data disclosures into accurate investment return figures (expectancy).

I know this from my coaching experience because whenever I ask a client (many are very sophisticated) what interest they earn on their whole life policy, they’ll tell me the “headline” figure. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

For example, let’s imagine a fictitious 68 year old female client named Ashley with a $250,000 whole life policy, just so we can quote real numbers.

She would probably tell me something like, “Todd, I make a guaranteed interest rate of 2.5%, but that’s the worst case scenario. It actually earns more like 4.75%.”

Let’s see if she’s right…

We’ll start the analysis in the guaranteed values column on the left side of the table above, where the illustration shows a 2.5% guaranteed interest rate.

Take special note of the Premium Outlay and Cash Value columns.

Nobody needs to pull out a financial calculator to figure out that the owner isn’t quite making 2.5% on her money.

She has paid over $21,000 per year for 5 years, (that’s well over $100,000), and the guaranteed cash value in year 5 is only $79,556.

The same is true for the “Non-guaranteed” column.

A $21,848 contribution over 5 years at 4.75% interest should result in an end value of $120,123. So that column doesn’t quite add up, either.

So obviously there are charges here that are being taken from the policy.

Are they hidden? No. They are stated in the illustration, but the point is, people don’t notice them.

These fees include:

- Commissions

- Cost of insurance/mortality fees

- Policy fees

- Administrative fees

- And in the first 15 years, typically, surrender charges

Here’s a personal account from Matt Becker of MomAndDadMoney.com:

“With that said, there is actually a small guaranteed return on these policies, but even this is incredibly misleading. In the policy that was attempted to be sold to me, the “guaranteed return” was stated as 4%. But when I actually ran the numbers, using their own growth chart for the guaranteed portion of my cash value, after 40 years the annual return only amounted to 0.74% … The reality is that you can get better guaranteed returns from a CD that locks up your money for a shorter period of time and is FDIC insured.”

The reality is expenses matter, a lot! Let’s explore this further…

Whole Life – The Expensive Sister of Mutual Funds

Just to be clear, the life insurance industry is no more deceptive at reporting their numbers than any other financial industry.

You must be a smart consumer and look closely at the details to get the truth, because numbers can be used to deceive if you don’t understand them.

For example, mutual fund companies and other investment firms frequently report average returns rather than compound returns. The reason is simple: average return is always higher than compound return, so it makes the investment look more desirable.

The reality is compound return is the only number you can actually spend, thus it’s the only number that actually matters to an investor. Average return is a statistical fiction that doesn’t exist in your account because your money compounds, it doesn’t average.

The same is true with mutual fund expenses and 12b-1 fees. They are disclosed to you in unreadable documents filled with legalese so everything is above board.

However, they never show you the paper trail by providing the exact figures for how much you personally spent on those expenses and fees, and how much lower your account value is as a result.

Most mutual fund investors would be shocked to know that if they earned 8% in their mutual fund, the actual underlying portfolio they're invested in might have made 10-11% during the same period.

So where did the other 2-3% go? It’s hidden in the detailed expenses that were fully disclosed to you, even though you can’t figure out how to find the actual money lost.

Again, this is not some grand conspiracy theory. It’s how the financial industry works, and it’s all fully disclosed in the prospectus (contractual documents).

The problem is consumers (you) rarely know about or understand how to interpret the details of these documents, and even if you know what’s disclosed, it’s very difficult to translate back into tangible dollars and cents.

The game the pros play is to make the investment complicated, and then layer in expenses in disclosure documents that are difficult to figure out.

Complication alone is not necessarily bad, but it usually accompanies high expenses, which means it violates two fundamental investment tenets:

- Don’t invest in anything you don’t fully understand. If you don’t fully understand it, then you can’t possibly know the expectancy of the investment.

- Below average expenses are associated with above average returns. It’s only acceptable to incur investment expenses when they put more money in your pocket than they take out.

Expenses matter.

Small amounts compound over many years to become large amounts. Insurance actuaries are pros at figuring this stuff out and using that knowledge to structure policies that profit at your expense.

The bottom line is you want to pay attention to expenses and fees for all your investments, including your life insurance.

And you should never invest in something you don’t fully understand because you should only put capital at risk on positive expectancy bets. If you don’t understand it, then you can’t figure out the expectancy.

The Problem of Compound Interest

Staying with our compound interest reasoning, it’s also worth noting that one of the reasons for the meager returns in whole life is what happens during the first 10 years of the policy… minimal to no gains.

The problem with the math of compound returns is low returns in the early period are very difficult to overcome over the long term. You have to earn extraordinary returns in later years to result in an average compound return.

Again, this is all just the way the math works. It’s not an opinion. It’s inviolable math.

Unfortunately, whole life insurance wastes those first 10 years of compound growth. In fact, it’s the rarest of policies that will break even in the first 10 years.

That’s because the first 10 years are front loaded with heavy fees and expenses, causing you to lose valuable compound return time.

Whole Life Insurance Taxation – Are Withdrawals/Loans Really Tax Free?

Now let’s turn our attention to all the tax benefit claims of whole life insurance.

This is actually a valid return stream. Insurance companies have lobbied heavily to be the beneficiary of this government sanctioned investment return stream – tax advantages – so they can turn around and sell those tax advantages to you for a profit.

But again, the devil for determining the positive expectancy from tax benefits is in the details (read “complication”).

There are 4 essential phases to every investment that must be considered when talking about tax advantages:

- Contribution phase

- Accumulation phase

- Distribution phase

- and Transfer phase

For example, a typical 401k enjoys tax favored treatment in the contribution and accumulation phases, but can incur income tax liability in the distribution and transfer phases.

Whole life proponents like to argue that you get tax favored treatment in 3 of the 4 phases:

- Contribution phase

- Accumulation phase – cash value grows tax deferred in life insurance contracts

- Distribution phase – when it’s time for you to take money from your policy, you can borrow “tax free” from your cash value

- And Transfer phase – when you die, your policy benefit is transferred to your beneficiary(ies) income tax free.

(The really aggressive whole life proponents even go so far as to argue you can get tax favored treatment in the Contribution phase if you pull equity from your home to pay your life insurance premiums. The reasoning is your mortgage interest deduction provides a tax favored contribution. This is a highly aggressive strategy that puts your home at risk, so I would never encourage it.)

While the claims are technically correct, the devil is in the details (gee, have I said that before…?).

Let’s examine these details by starting with liquidity issues…

Before Taxation – A Word about Liquidity

Life insurance salespeople love to point out the liquidity of whole life.

They will boast that:

- You can access funds via policy loans, and you don't have to pay it back.

- Life insurance loans are a great place to turn for emergency funds, or even business loans, because the money belongs to the owner so there’s no “qualification” needed for the loan.

- And finally, loans are not subject to 10% early withdrawal penalties for taking funds prior to age 59 ½, as they are with IRA’s and SEP’s.

Agents will argue these benefits make life insurance an excellent source of lendable money at your convenience.

However, it’s not quite that simple. The problem lies in what happens to the policy once you borrow funds from it.

First of all, during the first 5-10 years of the policy, it simply cannot sustain withdrawals/loans. Yes, you can access the funds, but you’ll be charged interest and have to pay it back.

If you can’t pay it back, and you stop making premium payments, then any other cash value you have in the policy will begin to get eaten up by loan interest and cost of insurance.

Think about the illogic of the claims – most policies don’t have any gains for at least 10 years, so what’s the benefit of being able to withdraw money on FIFO tax status or borrow from your policy tax free if there are no gains to borrow?

What’s the benefit of getting to your money without an IRS early distribution fee of 10% if there are no gains?

Rather than pay all those premiums to the life insurance company, you could just stuff it all under your mattress and have instant access with no IRS penalty. It makes no sense if that’s really your goal.

Why would you want to use whole life insurance and have to wait roughly 15 years before you have any gains worth talking about? How’s that an advantage?

15 Years Later… Tax-Free, Liquid Access to Money, Finally! (Or is It?)

So when can we actually pull money out of a whole life policy and get this sacred tax-free income that insurance salespeople love to talk about?

Let’s say you’ve spent 15 to 20 years diligently paying your mandatory premiums, building up your cash value, and now you need some money…

There are 2 ways to pull money out of a whole life account:

- You can take a withdrawal (as mentioned earlier, in which case you’ll only pay taxes on gains after you’ve taken more than your cost basis)

- Or you can borrow from your cash value. Many owners withdraw funds up to their cost basis, to avoid taxation and loan fees, and then switch to loans.

In the first instance, there’s nothing impressive or unique about policy withdrawals. You’re merely withdrawing your cost basis, thus not incurring any tax since it was your money anyway. This isn't some great benefit you should get excited about.

However, the almighty whole life insurance policy loan is different. This is the feature that salesmen get excited to pitch as the great secret to investment income.

For example, let’s say you need some money to start a business or supplement your retirement. The good news is you can easily request a policy loan from your life insurance provider.

If you request a check, most companies will send it out within 2 weeks. (Although if you read the fine print, most carriers reserve the right to hold withdrawal or loan requests for up to 6 months before they pay.)

What’s really cool about this loan is that it’s low-hassle, you can usually get the money quickly, and your insurance carrier won’t be sending you a 1099 for taxable income received, as long as your loan amount doesn’t exceed your cost basis. That’s all fine and good.

So you’re happy to get your tax-free loan, but what’s happened to your policy?

- Generally, policy loans reduce the policy death benefit.

- Generally, your loan is accruing interest. You need to pay it back (plus the interest), or risk a reduced death benefit or even policy lapse (see #4).

- Your policy loan generally decreases your cash surrender value.

- When the loan balance exceeds your cash value, your premiums may increase to maintain the same death benefit. If you can’t pay the increase, your policy could lapse.

- If your policy lapses, 100% of all “tax free” monies ever taken are taxed as ordinary income.

None of this is necessarily bad for you unless your specific actions and situation make it a problem.

If you’ve accumulated a lot of interest and dividends, then your policy may have grown to the point that it can support the ongoing cost of insurance, and it might even support a 4% spend rule.

If you haven’t, then you could have a problem.

Again, notice the level of complication hiding all the fees and expenses. Think about how each rule impacts the expectancy of the investment. It’s so difficult to sort all this out that even the experts disagree.

The Death of a Whole Life Policy and Its Tax Benefits

The next issue we run into is the difference between theory and reality.

Whole life insurance salespeople pitch you the policy based on illustrations and tables that assume you withdraw or borrow from the policy according to perfectly designed plans.

Again, life happens, and the policyholder may need money earlier than expected, or more than expected.

One of the points I make in my book about the 4% Rule and Safe Withdrawal Rates In Retirement is that we have no idea what inflation will be like 20-30 years down the line, or life expectancies, or interest rates.

The future is unknowable.

But if you look at the whole life illustrations provided during the sales pitch, it shows a perfect pattern of premium payments for X number of years, and then shows a perfect distribution pattern with the exact same amount taken each year.

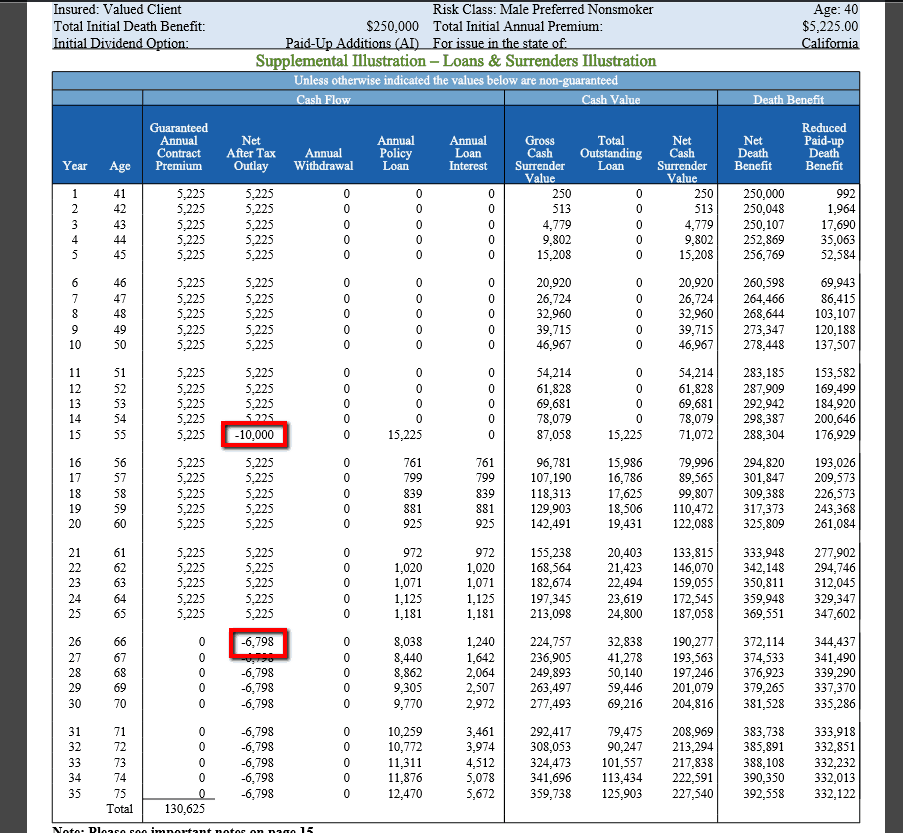

Take, for example, this sample whole life illustration for a 40 year old male, who pays $5,225 per year for a $250,000 policy.

The illustration shows 25 years of premium payments, and then shows him pulling out policy loans of $8,313 per year to age 100.

… so he pays his premium every year without fail, and then pulls out the exact amount for the rest of his life.

At first glance, it doesn’t look too bad. The policy seems to support an $8,313 per year loan amount for life off of a cash surrender value of $213,098. That’s almost 4%, and since it’s tax free money, it’s even more valuable, right?!

But do you see a problem here?

First, it’s important to note how there’s non-guaranteed interest and non-guaranteed dividends being credited to the cash value, which, in the case of interest, could be lower than illustrated, and in the case of dividends, might not happen at all.

Yes, there are many carriers that have been around for hundreds of years who pay dividends every year, so it’s almost as if they’re guaranteed, but they aren’t.

The cost of insurance also isn't guaranteed. The numbers above reflect what would happen if all goes according to the illustration.

Here's the “non-guaranteed” language at the bottom of the illustration:

Remember, I said to read the fine print.

The other problem here is the “never-miss-a-class, straight-A-report-card” policy owner who paid $5,225 per year for 25 years in a row, without missing a payment.

I don’t know about you, but my life hasn’t operated even remotely close to that level of certainty and perfection. Has yours?

Agents will say that you can add a “waiver of premium” rider, in case you happen to become disabled, which allows you to stop paying premiums, but that hardly solves most real world problems. What if you lose your job? What if you need to bail out a family member?

This should be particularly concerning for whole life “investors,” since the only way to avoid collapsing their policy when they start withdrawing funds is to take small amounts, probably not exceeding 3-4% of their cash value.

If they stray from that formula, as many do, then big problems can develop.

Watch what happens to the illustration above if “life happens,” and instead of paying every year for 25 years, you can’t afford to make a premium payment in year 10, and instead, have to take a $10,000 loan.

*Examples provided are illustrative only and should not be considered an offer for insurance. Premiums and policy performance varies by company. Not available in all states.

You can see the estimated amount available for lifetime loans drops to $6,798. That’s a big difference from the first illustration. Let’s see the math.

With one simple deviation from your perfect plan, the amount available for supplemental retirement income has been reduced by 23%.

It’s this severe because even though we pulled out only $10,000, our policy costs didn’t decrease. We still had to pay the cost of insurance associated with supporting a $250,000 death benefit.

Notice how severe this impact is compared to more straightforward investments that don’t have the life insurance wrapper.

**Please note I have not taken tax considerations into account in the above charts, as my intent was not to show how much more or less you could earn by choosing an alternate investment, but simply to show you how an alternate investment is not impacted as severely by unexpected changes, particularly when they occur early in the plan. I could have skewed this even more in favor of the “alternate investment” if I had adjusted the contribution for its pre-tax equivalent. In the same breath, the reverse is true for the tax-free vs. taxable distribution of the two options.

The key distinction between life insurance and other competing investments is life insurance is just a contractual obligation. If life goes awry when owning other investments, you can adjust your withdrawals because you control the asset.

You might have to adjust your living expenses because of withdrawal errors, but at least the corpus of your investment will not be affected.

But with whole life insurance, you’re bound by the contractual obligations of the policy, and may not have the same luxury.

What typically happens with whole life is the owners who purchased the policies were told to expect to rely on them for retirement income.

Upon retirement, they stop making premium payments, borrow far more than the amount of annual interest and dividends the policy can support, and cannot afford to pay back the loans. These loans typically accrue interest at 4-8% depending on the company, which leads to hefty unpaid loans.

Ultimately, the loan must be paid back. (Or the owner must at least pay increased premiums to keep the policy in good standing.)

Often the owner can do neither, and the policy lapses. When that happens, all of the tax-free monies received over the life of the policy suddenly become taxable.

It can be a very bad situation.

Did I remember to mention the problem with complicated terns and how the devil is in the details?

Sample Whole Life Buyer

For example, let’s consider Sam, a 34 year old man in good health, who needs life insurance to provide income replacement for his wife.

His agent sells him a $500,000 whole life insurance policy for $4,790 per year. It’s a lot of money for Sam, but his advisor assures him it will not only help him accomplish his insurance goals, but points out that it will offer him the additional benefit of tax-deferred accumulation and tax-free withdrawals via policy loan, should he need extra cash in retirement.

The sales pitch includes an illustration of guaranteed death benefit and cash value totals that looks something like this:

As you can see, 20 years into the policy, Sam has invested $95,808 (premium outlay) that’s now worth $111,245 on a guaranteed basis.

His agent would point out that his policy would likely earn dividends (non-guaranteed), which would be re-invested into the policy and help grow the cash value.

If that were the case, and if this policy were truly liquid, and these funds were truly tax-free, this might not be so bad after all.

… But in fact, that’s not the case, as explained above.

Sam doesn’t truly have access to $111,245 on a tax-free basis in year 20. In fact, if he withdraws all of the cash, the policy will lapse, and he’ll be taxed on the growth.

If he borrows all the cash, he’ll immediately be hit with a severe premium increase to keep the policy in force, or it will lapse.

If he borrows only 80-90% of the cash value, the policy may not lapse immediately, but would require additional premiums to pay back the loan and pay for the cost of insurance.

So you see, it’s not as if once you’ve accumulated some cash value, you really have unlimited, tax-free access to the cash.

Your access is limited, and you have to pay for access to it.

So to conclude this section, policy loans only work if you pay them back, or take out small enough amounts that the loan never overtakes the cash value for the duration of the policy.

If the loan overtakes the cash value, then you put the policy at risk of going belly up.

Getting this right requires constant monitoring and requesting new “in force illustrations” to ensure the policy is not in danger of lapsing, and that no further premiums will be needed.

Do you have the expertise or desire to follow through on that in your retirement?

Misconception – Whole Life is “Risk Free”

While whole life may offer guaranteed interest, a lot of people misinterpret that fact to imply that cash value always increases – never going sideways or down.

Given the expense threshold of the policy, that obviously can’t be true. If you’re not totally clear about how this works, then just stop paying your premiums for a couple years, and you’ll quickly see that your cash value certainly can decrease.

Remember, administrative fees and cost of insurance continue getting deducted from your policy whether you pay premiums or not. This isn’t just an investment. It’s life insurance also, and there’s a cost for that insurance.

Not only is an ever increasing cash value not a sure bet (despite guaranteed interest), but you want to take your investment return analysis one step further and realize your true investment objective is to increase purchasing power net of inflation and outperform other investments competing for your scarce capital.

In other words, it’s not just a question of whether or not you’ll make money with your whole life insurance policy (which is not a certain bet), but it’s really a question of whether or not you’d be better off investing that money elsewhere.

That’s a much tougher threshold to overcome…

Opportunity Cost

For example, do your recall our earlier example of 34 year old Sam buying whole life insurance?

He paid $4,790 per year, and by year 20, he had a guaranteed cash value of $111,245. That’s an ROI of less than 2%.

What if he bought term life and invested the difference in premiums?

At Sam’s age, he could purchase a $500,000, 20 year term policy for just $249 per year. (If he’s following my strategies… paying down his debts, spending money wisely, and saving for retirement, he shouldn’t need coverage longer than that.)

This is a true measure of what Sam’s real cost of insurance should be.

Again, I’m putting this in bold to drive the point home. You want to separate the life insurance component of a whole life policy from the investment wrapper it’s contained in to sort out the cost versus benefit equation.

Remember, complication is how the financial pros hide unnecessary expenses, and combining insurance with investment is very complicated.

When you separate the insurance from the investment, what you quickly see is Sam is paying $4,541 per year more than he has to for his insurance needs.

If he were to take the savings and invest it at just 6% after tax, he would have accumulated $167,043 after 20 years. You can run these calculations at various ages and face values, and the results are extraordinarily consistent. In all but the rarest of cases, term wins.

What Should I Buy Instead?

Again, if you are following my strategies on this site, you should have no need for life insurance beyond your working career.

The message is straightforward – KISS (Keep It Simple, Sam). Don’t collapse the life insurance component with the investment component. Separate them to see the true cost.

Term insurance can be a good idea if you have dependents who rely on your income, but even that can be dropped once you’ve accumulated enough assets to ensure their well-being in the event of your death.

However, there are other life situations where permanent insurance is needed for estate planning or charitable giving.

For example, it's common for very wealthy individuals to purchase life insurance to pay federal estate taxes due upon their passing.

In 2016, estates valued at $5.45 million or less are excluded from federal estate tax. Any amount over that is taxed at 40%. The exclusion amount is doubled for married couples.

So if an individual has a net worth of $25 million, for example, his federal estate tax liability would be over $7.8 Million dollars. (After the exclusion amount of $5.45 million, that leaves $19,550,000 subject to a federal estate tax of 40%.)

If you're fortunate enough to face that problem, then lifetime guaranteed coverage is a potential solution.

Many independent agents offer a form of permanent life insurance called guaranteed universal life insurance.

It offers guaranteed lifetime protection and guaranteed level premiums, but because the policy isn’t mixed up with an investment component that grows in cash value, it can be purchased for half the cost of whole life (or less).

For cases like this, many wealthy individuals opt to purchase life insurance to cover the future tax liability and keep their estate whole.

Take, for example, a 60 year old man in this situation. He’s worth $25 million and his estate will owe $7.8 million in federal tax within 9 months of his passing.

If he wanted to avoid a $7.8 million reduction to his estate, and he’s in great health, he could buy a guaranteed universal life policy with guaranteed level premiums to age 95 for $97,188 per year (as of this publishing date).

If he lives 21 years, as the Social Security Actuarial table predicts he will, he will have paid just over $2 million in premiums for the life of his policy, and the death benefit will effectively wipe out his estate tax problem.

Obviously, this a simplified example. It doesn’t factor in what he could have done with that money for those 21 years (opportunity cost), or the fact that his estate would likely be increasing over that time frame, increasing his need for coverage.

The point is to show you how affordable guaranteed universal life can be if you do have a permanent need.

Tony Steuer, author of “Questions and Answers on Life Insurance”, only sells guaranteed universal life. He says:

“When I consult, if there’s a permanent need for life insurance, I always go with a Guaranteed Universal Life (GUL) recommendation – pure insurance and nothing more. Life insurance is the only type of insurance where someone expects something back if there’s no claim. With homeowner’s insurance, policy owners are perfectly happy when their home doesn’t burn down and they don’t have a claim. That’s how GUL’s work. They only pay out when the insured passes away.”

Is Whole Life Insurance the Best Type of Life Insurance for Estate Planning?

Another misconception is that whole life is a good financial vehicle for estate planning. As discussed in the previous section, if permanent insurance is needed, the best value in coverage is guaranteed universal life.

When Does Whole Life Make Sense?

It should be clear by now that for 99% of individuals, whole life insurance does not make sense.

However, there is a rare combination of circumstances where whole life insurance might work:

- The policyholder needs permanent life insurance protection,

- Is extremely wealthy and has exceeded the contribution limits of competing tax-advantaged investment plans such as the 401K, IRA, HSA, or for the self-employed, a Solo 401K or SEP,

- Can easily afford the planned premiums,

- Is not concerned with rate of return…

- …and values the less tangible benefits from the policy such as asset protection, or for businesses, higher employee retention, or simpler (or more cost effective) administration of defined benefit plans.

Remember, I didn't say whole life insurance is always a bad deal. It's not. There are always exceptions, and those exceptions are best illustrated by clients placing a high value on the ancillary benefits provided by the policies (not the straight investment return or life insurance itself).

In a recent report conducted by The Newport Group titled “Executive Benefits: A Survey of Current Trends,” the group determined that within businesses with $1 billion or more of revenue, permanent life insurance (often whole life) is used to fund 82% of supplemental executive retirement plans and 73% of Non-Qualified Deferred Compensation plans.

Businesses use cash value life insurance to fund their executive retirement plans not for rate of return or liquidity, but for completely different reasons that are beyond the scope of this article. I’ll mention them in passing, just to illustrate:

- They set up a “split dollar” plan providing some death benefit protection to the business as long as the employee or key executive works for the business.

- Employee retention benefit.

- In some cases, businesses find it's cheaper, or they run into fewer ERISA compliance issues, when life insurance is the funding vehicle.

In other words, the motivation for the purchase is an ancillary benefit of the policy other than the expectancy of the investment. This is a key point.

Another example of this type of motivation is when a wealthy individual chooses to fund a whole life insurance policy with large amounts of premium for asset protection reasons.

Historically, creditors and plaintiffs have had a difficult time attacking life insurance cash values, since the purpose of that money is to pay for life insurance expenses.

Notice how the motivating reason is not the expected return of the investment. It’s the legislated value of ancillary benefits, by law, that motivate the purchase.

Get This Article Sent to Your Inbox as a PDF…

Agent Arguments

Okay. I’ve covered a lot of territory in this article. Now it’s time for all the insurance agents to jump in and rebut everything stated and prove what a great deal their insurance products are for consumers.

Readers should understand they are salesmen for a reason. They make their living by being persuasive, and I fully expect amazingly persuasive comments showing how most of what I said is nonsense and I don't understand the business and made egregious errors and don't have any clue what I'm talking about.

So let’s prepare the normal (not a life insurance geek) reader for the usual types of persuasive arguments used to refute everything written here so that you’re well-armed to deal with the onslaught:

- The Circumstantial Argument – They’ll cite examples where they personally, or maybe their clients, got a great return on their whole life policy. Yep, it’s entirely possible. There are always exceptions. However, that doesn’t change the general principle that it’s not right for the majority of middle to high income individuals.

- The “Properly Structured” Argument – These arguments consist of various statements about whole life only working if it’s set up properly. For example, you must have the right agent using the right policy from the right company. Or if you structure it for maximum cash accumulation, or direct more premiums to paid up additions, or buy this or that rider, or pay up your policy over 10 or 15 years instead of over your whole life, or if you take your cash as a life-only SPIA how much more money you’ll end up with, etc. While I agree some agents will set up whole life policies for better success than others, and that some companies offer products superior to others, these don’t change the irrefutable facts. Regardless of what you do, you’ll still have the problem of forced contributions, limited liquidity, and a policy that usually won’t break even for 10 years. Will careful structuring help? Of course. Does the fact that careful structuring is necessary for it to work prove the issue about unnecessary complication raised in this article? You betcha! Does it prove my point that the devil is in the details to calculate the expectancy of the contract? Absolutely yes!

- The “Better Than Nothing” Argument – Agents defend selling whole life insurance because even if whole life isn’t the perfect investment, it’s better than nothing, and people would be better off investing in this “forced savings plan” than doing nothing at all. Yep, I absolutely agree that it’s better to pay premiums into a whole life policy than spend your money on lattes, but to be fair, when analyzing any investment opportunity, the deciding factor usually isn’t whether or not you get a better return from the proposed investment vs. pissing your money away. The real question that must be addressed is whether the investment outperforms competing investments. Lattes aren’t an investment. Anything is better than nothing, but that’s not saying much.

- The “Burned by Term” Argument – They’ll cite examples where people got burned by buying term instead, and down the road, after their level premium period expired, they still needed coverage, but couldn’t afford to buy permanent coverage in their old age. They’ll argue that people should lock in their permanent rates when they can (the younger, the better). Yep, that's true also. But they knew that fully disclosed risk when they bought term. It's not a case for whole life, but it could be argued in favor of guaranteed universal life.

Realize also that many agents love whole life, not only because they make great commissions from selling it, but because some agents really do believe in it.

Just take what they say with caution. See if you can uncover all the details and complication well enough to develop a full understanding about the investment expectancy of the policy. It's not likely.

Note to Agents: My only request with all the expected critiques is you please be respectful to my audience by focusing on facts and providing information that expands the knowledge base.

Conclusions

The lesson learned from analyzing whole life insurance is pretty straightforward and can be extrapolated as a general principle to other “Swiss Army Knife” investments like variable annuities as well.

Complicated investments are usually complicated for a reason. When the insurance actuaries mix life insurance with a savings account with guaranteed income and throw in tax benefits and borrowing all into one wrapper, even the experts can get confused.

The facts and numbers can be twisted in many different ways. Just trust one thing: life insurance actuaries aren’t dumb.

They design and price this stuff for a living, and they represent the opposite side of the deal from where you stand. The goal is insurance company profit, pure and simple.

And the only way they can profit is to construct a package that sounds desirable enough to the consumer to motivate him to hand over his money, yet price it in a way so that the insurance company and the agent selling it get paid.

Stated simply, it must be a positive expectancy bet for the insurance company and negative expectancy bet for the buyer (on average), otherwise it won’t be profitable to the company.

That’s not to say all life insurance is bad. Quite the opposite is true, as long as you use life insurance to insure those risks you can’t afford to take.

In other words, the general rule is to use insurance as a risk transfer tool. That’s what it was originally designed for before slick salesmen and actuaries figured out how to redesign it as investment packages with tax benefits and complicated rules to broaden the sales appeal.

The undeniable truth is that it’s extraordinarily difficult for consumers to separate out all the costs and figure out what benefits they really need versus what they’re paying for.

These complicated investment products sell well because the pitch includes a smorgasbord of benefits all wrapped into one investment product, albeit at a cost.

They sound appealing because you get so many things that no other investment provides – guarantees, tax benefits, asset protection, and even a little life insurance thrown in for good measure. Few consumers have the time or financial savvy to dig deep enough to figure it all out.

Slick salesman use advanced persuasion techniques like the framing tools mentioned above (and likely used in the comments below) to organize arguments that sound undeniably true to promote their policies (read “contracts”), while simultaneously failing to disclose the multitudes of rules and complication that must be fully understood to really know the investment expectancy of the product.

Related: 5 Financial Planning Mistakes That Cost You Big-Time (and what to do instead!) Explained in 5 Free Video Lessons

If you’re one of the unfortunate people who was sold a bill of goods by one of the big name life insurance company agents and it hasn't measure up to expectations, then consider cutting your losses by using your cash value to fund a guaranteed universal life policy instead, or by cashing in your insurance and buying term instead.

I hope this information on whole life insurance has helped you understand the issues at a deeper level so you aren’t easily swayed by the narrow framing arguments commonly provided.

This is business, and like most business decisions, it’s really common sense when you get right down to it.

Complication is generally used to obfuscate the facts and distract the consumer from the obvious truth. For that reason, be wary of complication.

If you can’t fully understand it, then don’t invest in it.

"Discover The Comprehensive Wealth Planning Process Proven Through 20+ Years Of Coaching That Will Give You Complete Confidence In Your Financial Future"

- Get a step-by-step action plan to achieve financial independence - completely personalized to you.

- How to live for fulfilment now, while building wealth for the future.

- No more procrastination. No more confusion. Just progress and clarity

Expectancy Wealth Planning will show you how to create a financial roadmap for the rest of your life and give you all of the tools you need to follow it.

Life insurance is only for people who have families. For singles who don’t intend to ever get married and have no dependents it’s a complete waste of money.

I am a life insurance agent sir. It does help for people who do not have the opportunity to save their money. For example, a family of 6 where both parents work two jobs and still cannot afford a simple lifestyle cannot set aside this money if they want their family to enjoy life. It helps people who might develop some sickness later down the line and they have to use all of their saved money to pay doctor bills. Life insurance helps for those instances where a person does not know what will happen in the future; and no matter how much planning you do, you are not God and do not know what will happen. Just saying.

ShanaSanders I stand by my opinion that it is of no use to single people who have no dependents and have no intention of getting married.

andru08

berneigh andru08 As I stated in the article, I want the comments civil and respectful. Life insurance posts have a history on the internet of getting out of hand in the comment section so I’m requesting all comments are an attempt to add value with additional opinions and facts without being derogatory or abusive. Thank you.

Todd,

I was not being abusive nor was I being derogatory. I was merely stating an opinion and a fact that applies to me and I think may apply to other singles with no dependents who have thought things through. It does not make any financial sense to stash money away for the care of dependents if there are no dependents to take care of after one’s demise. It makes much much better sense to invest it for early retirement.

I have never had nor will I ever purchase life insurance. I have given much thought to it and don’t see any financial value to do so. It is also true that I have already made all the necessary arrangements of donating my remains to science when I meet my demise.

If anyone was being disrespectful, I feel it was @berneigh. If my methods and decisions do not match up with the general populace there is no need to bring my parents into it. That was terribly impolite.

andru08 Exactly my point. I was addressing @berneigh

Todd,

I think your analysis is spot on, and that’s coming from a life insurance agent. Agents try to improve these policies by structuring them differently, adding riders, directing more money to Paid-up Additions, but ultimately that only makes them incrementally better, like putting lipstick on a pig. All whole life policies end up having the liquidity concerns and forced contribution arguments you outlined. Well done!

ChrisHuntley Thanks Chris!

Thanks, Todd, “I wish I’d read this years ago!”

When I took over my Dad’s finances in 2011, his files included a three-inch stack of 45 years of correspondence with the whole-life insurance company.

They were constantly bickering over the loan amount, the interest, the fees, and the cash value. Dad reached financial independence in the 1980s and no longer needed the policy, and neither did us beneficiaries.

I wish he’d been foresighted enough to cash out and spend it on himself, or at least invest it to pay his long-term care expenses.

Instead in 2010 he did exactly what you suggest: he converted to a guaranteed universal life policy. Which he also does not need.

You’ve saved me a lot of time drafting a chapter about whole life in my book to help military families make good decisions on insurance policies… now I’m just going to link to this post.

The Military Guide Thanks Doug! Sorry to hear about your Dad’s trials and tribulations with the insurance company. That’s one of the challenges in having little more than a contractual obligation where the other party holds all the cards. Yes, it is a legally binding contract that they can be held to, but there’s a lot of interpretation of language and calculations where they have the upper hand. Life is short and sometimes the battle to justice just isn’t worth it.

InvestorJunkie Whole life insurance is the next best investment to time shares. Total Waste.

Outstanding summary Todd. The complexity and incentives almost guarantee most of these products will be sold inappropriately.

HapyPhilosopher Yeah, the complexity is mind-boggling. I’m always amazed how someone will do a simplistic analysis to compare cash value growth against competing investment alternatives as if that’s all there is to it. No discussion about what happens when you actually use that cash value and how it impacts the policy and what rules are associated.

Financialmentor Yes. I have tried to talk several people out of various of these complex products after talking to a friend of mine who is a financial advisor. He has many horror stories about these instruments collapsing on people not being careful with them in retirement and having massive tax liability at exactly the worst time.

Interesting post, a bit long winded, but info I wish I had in ’07. One piece missing, that I found, was what do I do now? Not sure how many of your clients are/were in the same boat as me, but I was pretty sure you may have remembered our conversations and they influenced this post.

So the question is, what does an individual do with ~$300k in cash value? As you mentioned, 63.7% of us have some variation of this issue: we have cash tied up in whole life making some form of “guaranteed” dividend, but as you identified, it’s not easy to liquidate or use that money.

We spent a lot of time talking about why I won’t create wealth in my insurance during our discussions, but missed the point that I’m already there. I have to continue making the premium payments, regardless of size, or it comes back to bite me. I have taken loans to buy rentals and use the difference in my returns to pay back the loans, but that’s really the only thing I can see that makes sense to do with the cash value. Even at that, I’ll have to work hard to pay down the loans, unless I buy, hold, then flip the properties, which again, puts the cash back into a policy that makes it hard for me to access, unless I’m happy with the 6.25% return and want to take that as distribution.

Granted, the article is written to educate future buyers of insurance, but can you comment toward those of us that did use this strategy and “fell for the pitch”? You mention cashing in the policy and buying term or universal life, but at my tax rate, that would be upwards of $90-100k lost in taxes. Is this the best option to “cut bait”?

LukeGrogan I was thinking the same things when I read it…If I and my wife are 10 years into a 20-year paid up Whole Life situation, what are we to do now? Cashing out is an option but feels a little silly. We have Term a well, but maybe not quite enough…

i would be interested to see how FinancialMentor thinks those of us in the middle should respond? Thanks for sharing.

AJMcFarland LukeGrogan There’s two challenges to answering (both of) your questions…

The first challenge is every policy and individual situation is unique. I can explain the issues with whole life insurance in a generic and educational way, but specific recommendations would be impossible because the form of communication must be 1-on-1 to properly assess the situation. Anything less would be a disservice to you.

BTW, it would also be illegal because that’s the domain of licensed financial advisors and insurance representatives – to give personalized financial advice.

However, the easy solution is to contact the guys referenced in the article for a free quote and consultation at https://www.jrcinsurancegroup.com/financial-mentor-insurance-quotes/ There are only 4 guys there and that’s all they do is answer the exact questions you’re asking. They charge nothing for the service and the feedback I’ve gotten is they’re super helpful. Also, because they’re independent they can represent whatever is best for you. They’re not beholden to one companies products.

Give ’em a try and report back how it goes. Let us know…

Hope that helps!

Financialmentor AJMcFarland LukeGrogan I’ll give it a shot – thanks.

Thanks Paul Hoke for the kind words and generous share. Glad the education is helpful.

Thanks for this detailed article. Its hard to find clear analysis of life insurance products. Do you have a perspective on using Whole Life with a Long Term Care rider? this is something i have been thinking about – viewing whole life as a proxy for some of a bond portfolio and using the LTC rider as a better option than the direct LTC insurance market.

BritEagle There are too many nuances and details to each policy and how those policies match up to each person’s situation to do questions like this justice in a comment. However, there are 4 guys at my affiliated resource – https://www.financialmentor.com/go/life-insurance – and that’s all they do. Their entire work is analyzing policies and matching individual needs to appropriate company policies. They’ll crunch the numbers with you, and they won’t charge you for the service so you have nothing to lose by taking your question to them…

Hope that helps!

I only read the beginning of your article, once I realize you don’t

understand how taxation of cash value life insurance, I stopped reading,

I have other emails to read.

If you invest in a company(mutual

fund or whatever vehicle you are using) you will always pay taxes on

earnings unless you are in a roth account. You can access the money tax

free only if you margin the account, that is definitely not cost free

and it can be risky.

If you invest in commercial real estate, you

buy a property for 100,000 if it is worth 1 million in 40 years, you

can go take a mortgage for 800,000k, assuming the rental income can

cover the payments. You will not pay taxes even though you put in 100k

and took out 800k. Try doing that in the stock market, you will get hit

taxes. Why do we allow this. Because thats how the tax code is written.

If you sell the property, you pay capital gains, if you borrow against

it, NO TAXES.

Life Insurance taxation is very similar to taxation

of real estate. in the example above. You invest money in life

insurance, it grows tax free, you take out a loan, you pay no taxes even

though you put in more then what you put in originally. The reason it

is a good idea has nothing to with your win loss analysis about the

insurance industry.

Now there are obviously risk characteristics

of whole life that are different than commercial real estate. The rate

of return on commercial real estate would be higher on average than a

whole life plan that primarily invests in government bonds. However,

there is no guaranteed rate of return in commercial real estate. You can

pick a lemon property and loose everything. You may not be able to get a

mortgage in 40 years if your tenants don’t pay rent, you have lousy

credit or other financial circumstances.

Credit check on whole

life loan, NO. Any limits because you have a outstanding loan somewhere

else NO. Any issues if you have bad credit NO. Any margin calls ever NO.

Any taxes on a loan you take out from Most likely NO. As an investment

is it inflation proof. Probably not, you are investing in governments

bonds, In the long run you should come even.

So smart tax savy

people would probably do both strategies. They understand the tax code

and use it to their advantage. This is pretty much how Donald Trump has 4

billion or 8 billion now. He has lots of real estate under debt and

lots of life insurance. If your analysis had any merit, Do you really

think Donald Trump or Warren Buffet would invest in such a lousy product

if your analysis was correct.

tunctanin Hmmm… so you didn’t have time to read the article, but you did have time to write an article length rebuttal selling insurance. Okay.

Had you bothered to read the article you’d see that I clearly include the

tax free and hassle free loan benefits you’re mentioning. With that said, I also point out that those same benefits are not without risk (something you failed to do).

You can always borrow from the policy,

but you’ll be charged interest on the loans. In addition, some companies

pay interest (but not dividends) on the collateralized portion of your cash

value. Ultimately if your cash value is not earning enough dividends and

interest to pay your loan interest and premiums, and you fall on hard times and

can’t afford to pay it out of pocket, you are at risk of your loan balance

accruing to the point where it lapses the policy.

Again, for ultra

wealthy individuals, premiums may never be a concern, and I understand they may

just want to get the easy access, low (net) interest loans, but even to get to

that point, they have to pay into the policy for years. Creating your own “bank”

does not come cheap. There is no free ride. Insurance companies aren’t dumb.

It should be self-evident to anyone reading your rebuttal that people at the wealth level of a Trump or Buffett that you use as an example to pitch the product would have zero value on your “NO” list of benefits – margin calls, credit checks, outstanding loans, bad credit issues, etc. All ZERO value to someone in that situation. The person who would benefit from your “NO” list is the same person most likely to run into problems with a policy lapse.

This is very typical of the way these types of products are sold. The arguments are compartmentalized and it takes an expert to separate out the parts. Unfortunately, (or fortunately for the salesman) most consumers aren’t experts and fall prey to arguments like you’re making.

What about bank on your self life insurance and other programs like this? What is your opinion about these?

ValeneDubbelman I purposely left that subject out of this post because it will take an entire article to dispose of it properly and this article was already too long. In the meantime, I think Michael Kitces provided a balanced and well-reasoned analysis here https://www.kitces.com/blog/bank-on-yourself-review-a-personal-loan-from-a-life-insurance-company-and-not-infinite-banking/

Hope that helps!

I need your help…purchased WL with Mass Mutual…Paying 500 a month for the next 10 years. 3 years into it though…want to stop. Just checked cash value and is at a 12,000. which I can take out as loan..Don’t want to. If I surrendered now, would you happen to know the consequences or the fees? I am obviously going to lose a chunk of money, but I do not want to continue loosing more in the long run…Should I surrender for cash now and take loss or should I continue paying?? Please help me. Thanks

Yes, look at the sidebar for the life insurance quote form. In the fine print underneath the “display quotes” or “view quotes now” button you’ll see a phone number. Just call that number and let the person know you came from my site so he knows you’re an educated consumer (they know these articles and what the message is). These guys do nothing but life insurance all day, every day so the person answering can walk through the numbers with you to decide what your best plan of action is. Each case will be different because different policies have different terms, rules, etc.. In addition, the decision will require an understanding of your real life insurance needs (not fabricated needs from a salesman) in the context of your overall financial picture to determine the best course of action. It’s not something that can be answered in a comment because the smart next step will vary based on your personal details and the policy details. But again, these guys are experts at this stuff and can walk you through every step of the decision so you know all the trade-offs and implications. Just call the number. Hope that helps!

Todd,